A common objection to any genetic engineering technology is, “Only the rich will get it!” This is a bad objection, and I will now explain why.

The particular genetic technology I want to focus on is embryo selection (which is actually not genetic engineering, but genetic screening), since this technology is available now, albeit at a VERY early stage. The particular genetic modification I want to focus on is increasing intelligence, which is the more interesting and controversial discussion.

(Super fast primer on embryo selection for intelligence: Traditionally, when a couple chose to do IVF, they tried to get as many fertilized eggs as possible in order to increase the chances that at least one is healthy enough to implant. Today we’ve got better at the whole process so now a couple will often have multiple healthy embryos to choose from. And with genetic screening costs coming down lately, couples who want to (and can pay for it) are able to have each embryo genetically screened so that for instance, the embryo with the lowest likelihood of genetic disease can be implanted. Along with genetic diseases, intelligence can also be crudely predicted from the genetic screen, allowing couples to implant the embryo with the highest predicted intelligence if they want to.)

The more fleshed out version of, “only the rich will get it” argument against embryo selection for intelligence goes like this: Embryo selection for intelligence will create huge advantages, but only for the rich, since they will be the only ones who can afford it. Therefore we should not allow it.

My argument against goes like this:

If a technology delivers demonstrable, large-scale societal and economic benefits, strong incentives emerge to make it widely accessible.

Embryo selection for intelligence, if effective, falls into this category.

Therefore, embryo selection for intelligence, if effective, will become widely accessible

Premise 1

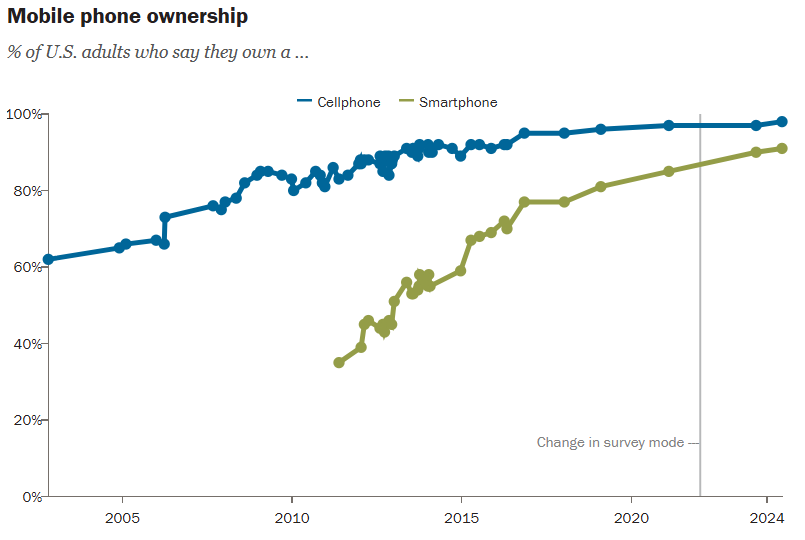

Let’s go through both premises, starting with the first. The thing about incredible, new technologies is that they all seem like a toy of the rich at first. When the first cell phone was invented in 1984 it cost $3,995, or $12,091 in 2024 dollars. They were gadgets only for wall street bankers. Today, everyone has one.

But what about technologies which are less so a nice-to-have like a cell phone, and something more like a need-to-have, like vaccines? Well the vaccine response to the COVID-19 pandemic is an emblematic example of a key technology being made available to everyone. The government stepped in with Operation Warp Speed and subsidized the vaccine so that everyone who wanted it was able to get it. If you are scared to “leave up to to the market” you need not be! If a technology is so valuable, like vaccines (and potentially embryo selection for intelligence, if proven effective), the government steps in to ensure its accessibility!

At a broad level, the reason technological diffusion occurs is because once a technology shows it’s potential for MASSIVE gains to our lives (cellphones, vaccines, antibiotics, computers, the internet, etc.) the same story plays out every time. The benefit is too big, the demand too strong, and the incentives too aligned. Once the technology is shown to work, pressure from consumers (and the government) will push it into broad accessibility.

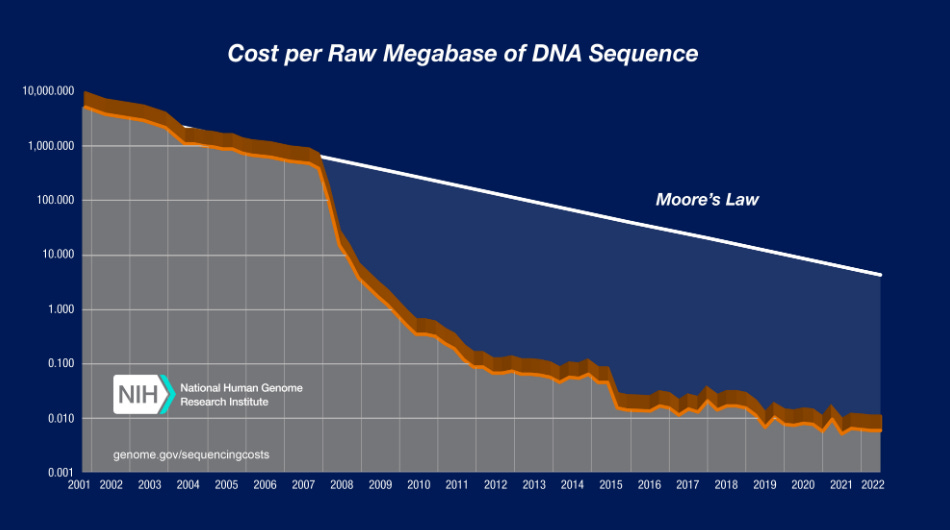

The two main drivers of this technological diffusion is the private markets, and government policy (showcased by cellphones and vaccines respectively). The private markets work to diffuse technology because of huge opportunity available to producers of technology! Econ 101 stuff. Producers are able to make a lot of money by offering the best product for the cheapest price. One of the most striking recent examples, which is also enabling embryo selection, is DNA sequencing technologies. The cost of DNA sequencing has decreased about a factor of a billion since 2001. It’s one of the most impressive examples of how quickly something can go from requiring entire scientific institutions and billions of dollars, to something your nephew can do in an afternoon (we’re getting there).

The other driver of technology diffusion is government policy. This comes into play when the positive externality SO large, and the public pressure is SO high, that the government implements policies to make it available to everyone who wants it, often by footing the bill. The important feature in the equation is the positive externality—basically each additional person’s use of a technology, engenders society-wide benefits Like with vaccines, the more people that get vaccinated, the more powerful herd immunity is, and it’s better for society, for wealth creation, etc. if people aren’t dying all the time! Or internet access—the entire reason the internet is useful is because so many people have access to it and can share information with each other. Society as a whole is better able to share information when more people have access to the internet. As it happens, embryo selection for intelligence would have huge positive externalities. Although it’s hard to explain what intelligence is exactly, there is something which humans have, that apes don’t, which allows us to do things like go to the moon and cure smallpox. Increasing intelligence could lead to unfathomable benefits, like the cure for cancer, ability to reverse Alzheimer’s, extension of the healthspan, discovery of better carbon capture technology to reverse climate change, better informed voters, better public policies, etc. etc. That’s why the government subsidizes these things; throughout history it’s been most common in the healthcare industry with things like vaccines, dialysis, and antibiotics, but also occurs in the telephone network and internet service industry. However, this doesn’t mean the government can just solve the problem. Many government interventions, like in the case of telecommunication and internet services, are often quite bad at delivering their promises. Operation Warp Speed is the best, modern proof-of-concept example we have.

Premise 2

Embryo selection for intelligence, if effective, falls into the category of a technology that “delivers demonstrable, large-scale societal and economic benefits.” This premise is pretty straight forward. The “if effective” part is the only wrinkle. If embryo selection for intelligence is, as proponents of “only the rich will get” argument are worried about, something that could create huge advantages for those who use it, then it would be in the category of something able to deliver, “demonstrable, large-scale societal and economic benefits”! If it doesn’t work, then there’s no argument to be had at all because who cares.

But what about other goods with big benefits which don’t diffuse to the broader population at all, like yachts? The reason that yachts don’t diffuse, as opposed to something like vaccines, cell phones, or embryo selection for intelligence, is that yachts are a very different kind of good. Yachts are a luxury good, so a lot of normal assumptions about prices and production are thrown out the window. The source of value of a yacht comes from the fact that it it’s luxurious and exclusive. It’s made of expensive materials with hand-crafted elements, typically custom made for the buyer. This is in direct contrast with a good like embryo selection for intelligence which has it’s source of value purely in functionality—to increase the likelihood of higher intelligence in an individual. A yacht’s value is not in functionality, a ferry can transport you just as well, but a yacht exists to be an opulent playground on the water. When a good’s source of value is in its function, like a car or cellphone or embryo selection for intelligence, the usual combination of factors come together to make it affordable to everyone.

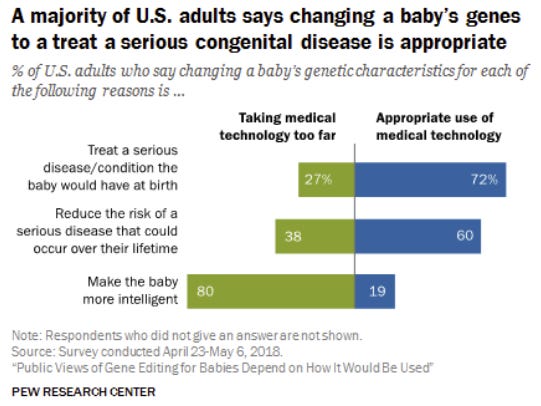

But what if it is effective and has big benefits, but people are still creeped out by it and adoption of the technology doesn’t become widespread? I think it’s true that people will continue to be creeped out by embryo selection, but it will simply mean that the diffusion of this technology will take longer than something like cell phones, as it will take time for people to accept it.

The rich will still be the only ones to get access at first.

This is true. The average cost of IVF treatment is $21,600, and then the genetic screening of these embryos is another ~$7,000. When it comes to specifically selecting for intelligence, the WSJ reports that one company offering this now is charging $50,000 (I imagine actually a lot lower than most people would have thought). But still, it’s by no means cheap. What does this mean for inequality? I think very little. Those who choose to use embryo selection for intelligence right now may indeed get a “head start” in some sense, but it would not lead to some crazy feedback loop where their descendants are bound to be our overlords. I agree, this sounds like a bad world! The reality is that 1) this technology is so new that no one knows if it actually works so people may just be wasting their money, and 2) the accelerating feedback loop of increasing intelligence for The Rich’s descendants is extremely improbable.

On the technology actually working, let’s say for instance, that a couple has 10 embryos to choose from (a slightly above average amount in embryo selection nowadays). The claim is that by selecting the right embryo, about a 7 IQ point increase would be possible. In actuality it’s probably lower than that because maybe the embryo with the highest predicted IQ is nonviable for other reasons, or because the implantation doesn’t work properly. It’s also probably lower than that because this is all completely brand new and has never been tried before and the startup offering the technology wants to put their strongest claim forward. It also doesn’t help that IQ is not a perfect way to measure intelligence, and the genetic screening we do is not a perfect way to predict it. So yeah, the whole technology is unproven and very speculative. It won’t be “The Rich” who are all using this technology at first, it will be small subsection of The Rich who have a high degree of openness and probably a bit eccentric.

On the scary feedback loop of ever-increasing intelligence for The Rich’s descendants, this is extremely improbable because of the huge time period in between loop instantiations! (i.e. kids having kids of their own). People are waiting longer and longer to have kids, so it’d probably be about 25 years until the first children who were selected for intelligence end up having kids of their own (whom they could select for intelligence if they wanted to). By that time, the price of these technologies will undoubtedly be far lower (see Premise 1), and adoption will be far greater.

To further illustrate, let’s say for the sake of the argument that due to the current $50,000 cost, only households which make over $250,000 per year can afford this technology (7% of American households). In a year from now, the cost will come down as more companies enter the industry and technology improves, which would mean that a higher percentage of American households could afford it. Maybe the price of embryo selection for intelligence would then be $45,000, and those who make $225,000 are now able to afford it (and we should expect the price to come down fairly quickly because in the production of new technology, the largest cost reductions are often more immediate). Repeat this procedure every year, year after year, and there simply is no dividing line between the haves and have-nots.

This is a very succinct intro paragraph. I find that refreshing